If you caught Civil War in theatres this last month, you have successfully completed your bimonthly consumption of dystopian media.

Your palette is freshly tuned to nihilistic visions of the future. You can find comfort knowing you fit right in with the rest of us: seeking comfort in the short term and dispensable while hope for widespread, systematic change feels increasingly like a detached fantasy.

This April Dev Patel gifted us Monkey Man. This action movie takes place in a caste-organized Indian city. Under the pressures of intense class divide, underground fight clubs emerge.

The Booker Prize winner of 2023, The Prophet Song, delivers the story of a painfully realistic war-torn Ireland. In it, civilians face vividly parallel conditions to that of the current war in Palestine. Each AI development inspires comments about having ‘seen a Black Mirror episode about this.’

Whether it’s class tension (Us by Jordan Peele), eco horrors (Don’t Look Up by Adam Mackay), or tech development (Her by Spike Jonze), we’re obsessed with portrayals of the worst-case scenario.

The modern dystopia

To be fair to writers and producers accused of fear-mongering, a dystopia makes for good TV! For decades, sci-fi fans have gathered en masse to watch their favorite characters reckon with oppressive governments and desolate planets.

The drama is rich and lore-heavy. But beyond that, what makes a good dystopian fiction is one that has an unnerving underlying truth. A contained work only lasts in public discussion when it cuts a little too close to the bone. It has its desired effect the moment the line between story and reality is paper thin.

You may remember feeling a pit in your stomach watching Civil War (2024) when a stray, machine-gun-wielding, true American soldier asks, “What kind of American are you?”, or maybe you’re still haunted by the “White Bear” episode of Black Mirror when audiences gather to capture a woman’s trauma on their phone camera.

Some images burn so vividly in the public mind that they inspire discussion for decades. George Orwell’s 1984 introduced us to terms such as “thoughtcrime” and “doublethink” as forms of ultimate state oppression. Even more prevalently, “Big Brother” often crops up in discussions of public surveillance.

These stories shout uncanny warnings of the future, but just like 1984, they tell us more about the state of the world in the present. Orwell created his chilling dystopia at the peak of the Red Scare. Just after WWII and with Stalinism still alive in the USSR, there was hardly a darker devil in the late 1940s than a totalitarian leader drunk on power.

So what can explain this most recent dystopian boom in media? There may be something deeper than entertainment value that resonates with such mass audiences.

A brief history of the dystopia

Inter-war Period

The German silent film Metropolis hit screens in 1927, most recognizable by its striking Bauhaus and Cubist-style set design. The film tells of a futuristic, dystopian city infected with a stark class divide. Riddled with poetic metaphors and political commentary, the film allowed viewers to draw parallels between the nightmarish 16mm depiction and the increasingly industrial capitalist economy that is reality.

Metropolis kicks off the dystopia genre in the 20th century. Closely after, the equally influential novel Brave New World debuted in 1932. If dystopic stories are to serve as time capsules, both signal growing awareness of the dangers of mass industrialism and the pitfalls of advancing technology.

Post-war period

As mentioned before, post-war fear of totalitarianism and communism inspired many genre classics, including 1984, Animal Farm, and Fahrenheit 451.

After perhaps a dry period in the 70s and early 80s, Margaret Atwood released her renowned novel The Handmaid’s Tale in 1985. She found inspiration in the philosophies of religious America and Ronald Reagan’s Republican party.

Famously, she claims her writing is not science fiction, but ‘speculative’ fiction. With this phrasing, she denounces any claims that her story of a patriarchal society that has stripped women of reproductive rights and individual agency is far out of reach.

Modern-day

At the turn of the century, dystopia writers played with evolving tech such as computing power and genetic modification. For example, The Matrix and Jurassic Park found mass success. You’ll likely remember the YA dystopia obsession in the 2010s with franchises, including The Hunger Games, Maze Runner, and Divergent.

However, today it feels like bleak future narratives are more than blips on the map. What-ifs surround us. If not directly centered around grim societal conditions such as Love Death + Robots, Severance, or Living with Yourself, plots play out with mass struggle in the background or as the punchline (see: the quick jokey shots at capitalism in Barbie).

Pessimism seems to be embedded in pop culture, and when it comes to tech development, we can’t stop speculating. But why?

Debunked promises

The promise of modernity

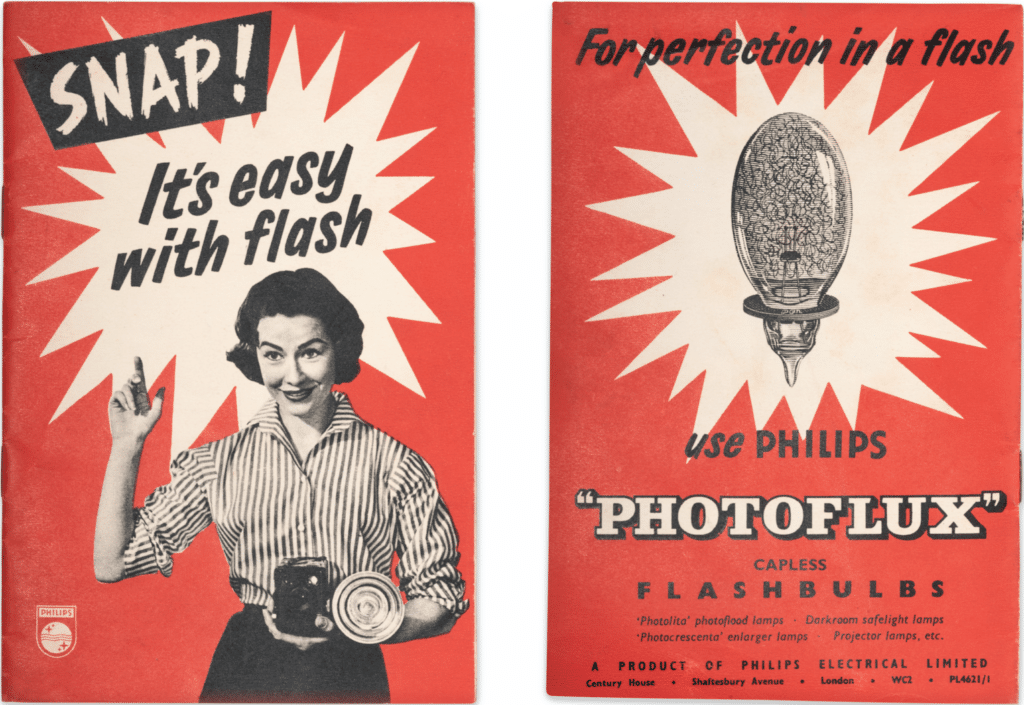

There was a time when innovation in the Western world seemed like it would never slow. A thriving economy and advancing technologies allowed for rapid adoption of modern amenities across the general population. From automobiles to toaster ovens, selling a ‘modern lifestyle’ became a trademark of the 20s and 30s.

World War II left America with a powerful production force, pushing consumerism to new heights. Again, the public was exposed to an unprecedented variety of products. Even further, stylized design democratized across several home and fashion products, allowing average consumers to choose the style of products they preferred.

This novel consumption culture within the context of wider tech trends like the space race and colored televisions certainly gave excitement to modernity and expanded the imagination for the quality of life possible.

Unanticipated outcomes

However, decades into contemporary living, advancing technology has not proven to be the catch-all solution advertisers claimed. Tools promising to make life easier for housewives, such as dishwashers and electric washing machines, instead aided in normalizing dual-income households so that women are expected to hold jobs while also tending to the home.

Additionally, despite communication being easier than ever, social isolation is on the rise, and mental health studies continue to reveal ways social media harms us.

It’s no wonder the ‘tech craze’ is met with skepticism by the average person who doesn’t have time to marvel at the technical achievements and instead worries that, for example, AI may replace entry-level or even college-educated positions. History has shown that technological promises of efficiency most often work in favor of the CEOs, not towards freeing up the average worker.

Proof of this colloquial disillusionment with modernity may be most apparent in recent consumer trends. In some sort of twisted cultural calculus, one of the most lucrative selling points today of a given product is an aspect of nostalgia that promises ‘simpler times’ and a more ‘grounded’ lifestyle. This is evident too in pop culture trends such as the Stranger Things mania and the romanticization of vintage fashion and interior design.

Gen Z and party politics

From a political standpoint, American brick-and-mortar political parties no longer resonate with incoming generations like before. Core promises of parties have failed the test of time in many eyes.

Republican’s free-market ethos and trickle-down economics prove largely baseless for the low to middle-income demographics, with the minimum wages remaining stagnant and debts on the rise. Democrats have yet to put forth major infrastructure plans thought to be necessary in the face of eco-catastrophe despite being the party for regulation and human rights. Today, younger generations are left directionless in a two-party system.

All of this to say, those looking to believe in a message or movement for a better future can’t avoid the gaping holes in what’s currently out there. If art is an accurate reflection of culture, it is bound to pick up on this cynicism.

The death of the utopia

The utopian storyline traditionally follows a classic format. The protagonists leave our faulted, chaotic reality and enter a starkly contrasting universe that is organized and equal. The protagonist may receive a tour of this alternate reality and come to respect its way of life. Literary scholar Barbara Klonowska recognizes that this genre “has practically disappeared” (2018: 12).

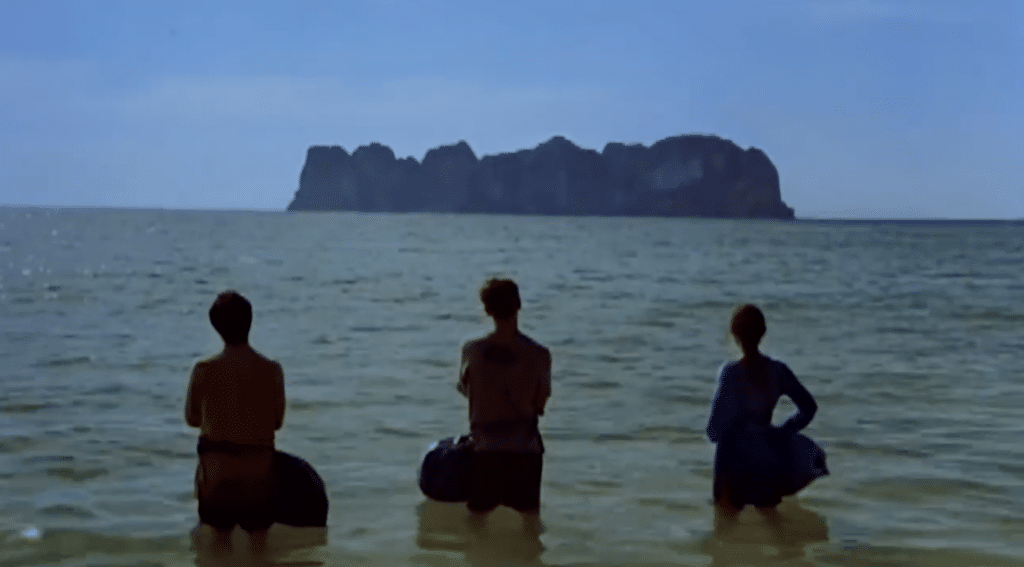

While you may look to Lost Horizon (1937) or The Dispossessed (1974) as examples, Klonowska argues what is left of this genre is only nostalgic or ironic conceptions of ideal societies. She points to The Beach (2000) as an example of a cinematic utopian story that turns ironic when the faults of human nature ultimately break up its idyllic setting.

Barbie (2023) serves as a recent example of how utopian narratives fit into contemporary culture. The entire intro to “Barbie World” exaggerates and plays into a ‘perfect’ society so that the punchline entirely relies on a mainstreamed cynical outlook from the viewer. Beyond over-the-top depictions like floating from room to room and spontaneous dance parties, we might ask ourselves: why is the ideal society so funny?

As Klonowksa theorizes, putting weight into an imagined utopia feels naïve in today’s world, and perhaps so ridiculous that it’s funny. Disillusionment is baked into a culture tired of politicians’ promises and accustomed to social disarray. For most audiences, dystopian storylines are rendered far more realistic.

Our dystopian world

Dystopian stories are everywhere and there’s no sign of retreat. Incoming generations face climate change, international tensions, political divide, resistant bacteria, and AI advancements–meaning there is no shortage of inspiration to pull from. But how should we regard this trend?

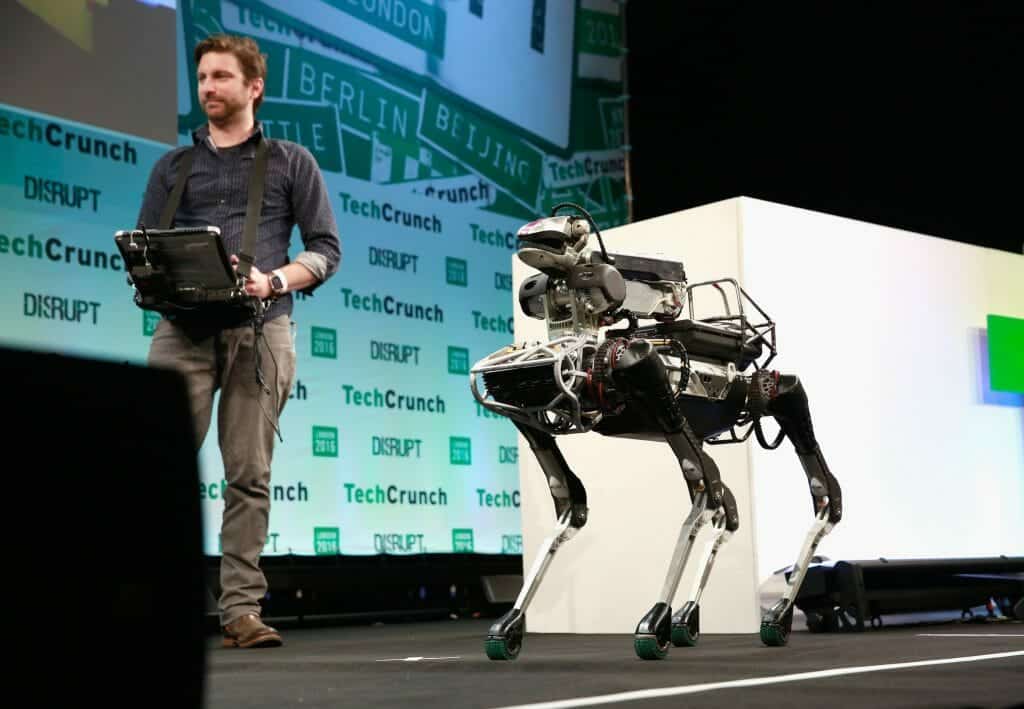

Writers have long imagined these dystopia worlds, predicting everything from death via asteroids to robotic cops, yet this earth still spins and robots are constricted to sweeping dust off the floor (for now). There is much to be wary of in the future, but we should also refrain from assuming the worst. The end of the world is far too juicy for Hollywood to stay away from; however, we shouldn’t detach from reality.

However, what history has told us is that these stories don’t exist without reason. A dystopia finds success only by resonating with wide audiences. They have a way of entering the public discussion and influencing how we understand the world around us. They tap into the collective psyche.

This dystopia boom certainly reflects our culture’s wide-held anxiety about the future. Forethought is heavy with dread and there is no clear direction or emerging leaders. But no good movie ends by giving up. While no one can blame you for being cynical, we can’t afford to be ambivalent.

There’s a big, messy journey ahead, but only we can begin to clean it up. So please, next time you’re in a theatre or reading a book and you get that dreadful, cursed feeling–that creeping suspicion that fiction could become reality–be brave enough to care. Let the message sink in, and maybe this tedious future of ours could have a chance.